Optimizer Architecture in Stable-Baselines3 for Safe Reinforcement Learning

Published:

You’re building a safe reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm involving rewards and costs. You now have a question: to train the policy, reward critic, and cost critic, should you use one optimizer like Stable Baselines3 (SB3) [1]? Or should you use separate optimizers as seen in many safe RL libraries like Omnisafe or SafePO [2, 3]? Or are there any other options?

One Optimizer vs. Separate Optimizers

With a single optimizer, we use a weighted loss: \(L = L_{\text{policy}} + w_1 L_{\text{vf.reward}} + w_2 L_{\text{vf.cost}}.\) Here, \(L_{\text{policy}}\) is the loss for a policy, \(L_{\text{vf.reward}}\) is the reward value function loss, \(L_{\text{vf.cost}}\) is the cost value function loss, and \(w_1\), \(w_2\) are weights balancing the trade off between losses. This approach combines gradients and control them only with the weights.

However, the problem here is that differences in magnitude bewteen rewards and costs could mess things up. Imagine rare safety violations produce large costs. In this case, \(\nabla L_{\text{vf.cost}}\) could dominate the gradient, messing up the update!

So, how could we fix this issue? A single learning rate with one optimizer might work well when losses have different scales. One solution is to use separate optimizers for each loss. But in this case, we have to consider which optimizer should update the share features. We could assign one of the optimizers to the shared features or we could assign all optimizers to the share features, but, this case updates the share features multiple times, which is generally undesirable due to instability.

Another idea is to use a single optimizer and assign different learning rates to different groups. For example, a higher learning rate for \(L_{\text{vf.cost}}\) could compensate for its larger magnitude. I actaully thought the opposite, but it seems larger steps are needed for meaningful updates on the loss with the larger magnitude. Much of the gradient information is derived by the loss. I ran some simple experiments in this Colab notebook

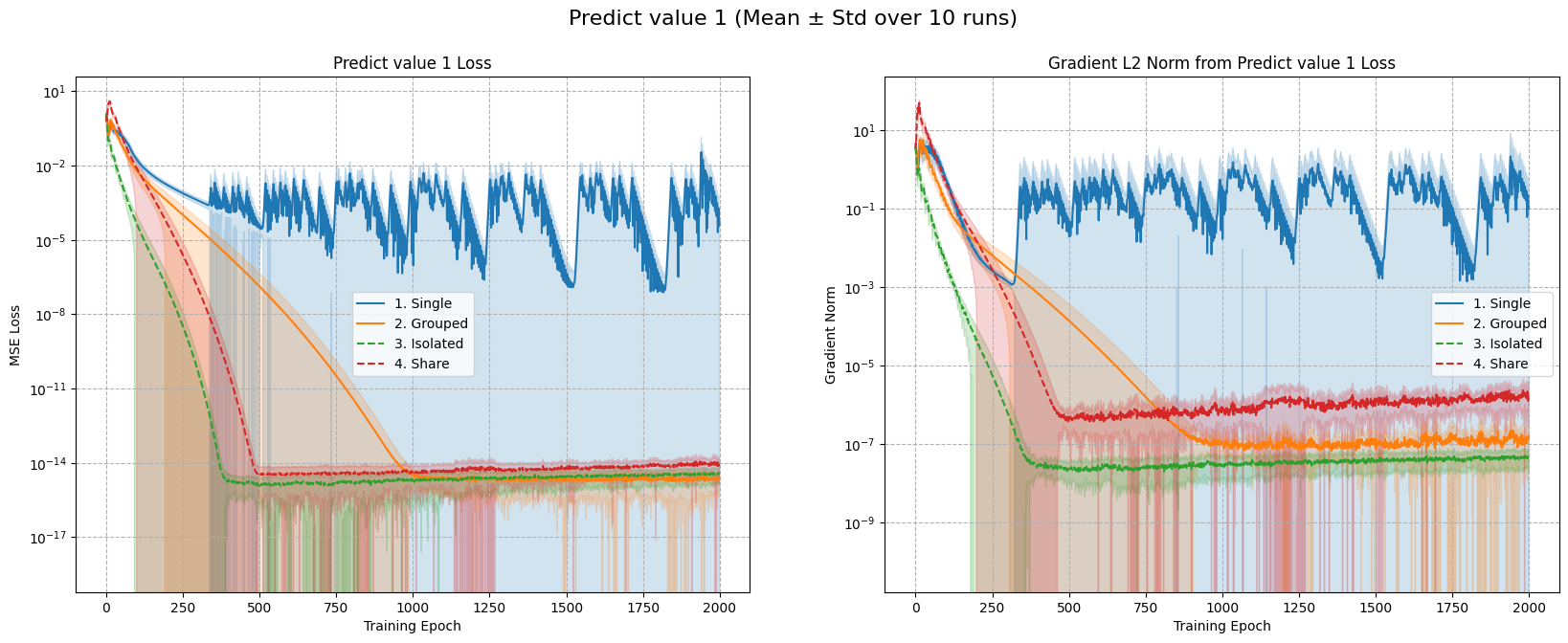

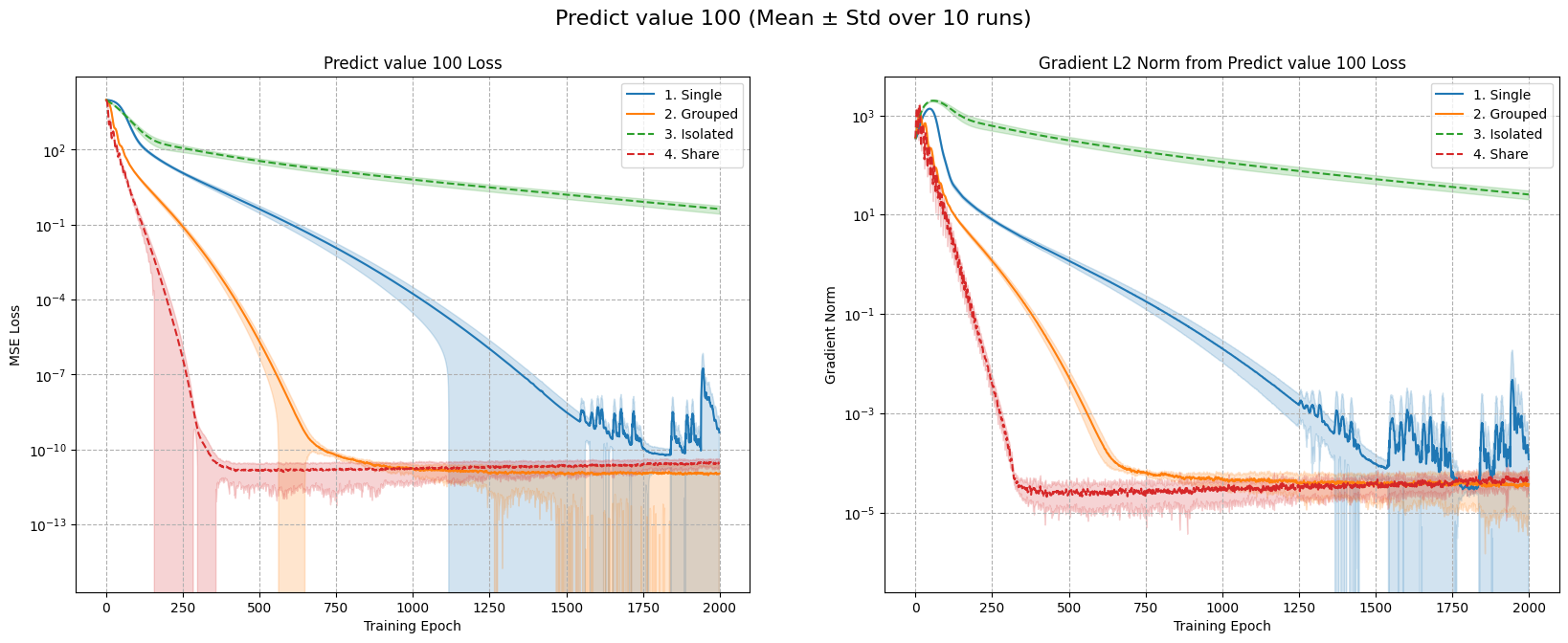

In these experiments, I used a shared network structure with two heads: the first head predicting a value of 1, the other 100. I tested four setups:

- Seperate optimizers for each head, with one of the optimizer for shared features.

- seperate optimizer for each, updating shared features with both optimizers (so shared features get updated twice in each step, assuming we call both optimizers in each step).

- One optimizer for everything, with a shared learning rate.

- One optimizer with per-group learning rates (e.g., higher rate for the second head, lower for the first).

Figure 1: Top: Predicting Value 1. Bottom: Predicting Value 100. Left: MSE loss. Right: Gradient norm.

Figure 1: Top: Predicting Value 1. Bottom: Predicting Value 100. Left: MSE loss. Right: Gradient norm.

The results in Figure 1 show that Case 2 converges faster, but updating shared features twice per step can cause instability, especially in complex problems. Meanwhile, Case 4 (one optimizer with per-group learning rates) converged a better solution as the optimization steps go further.

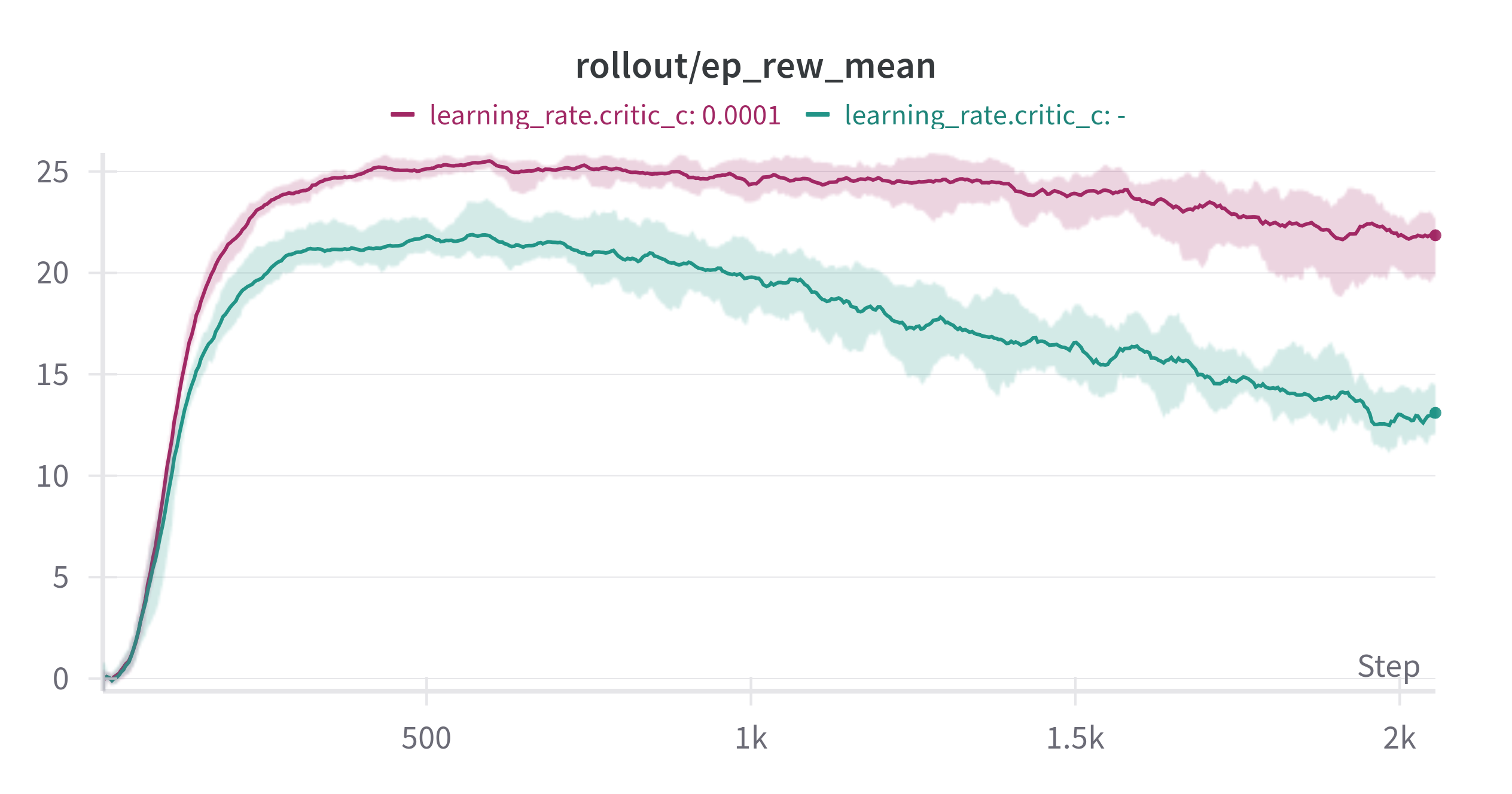

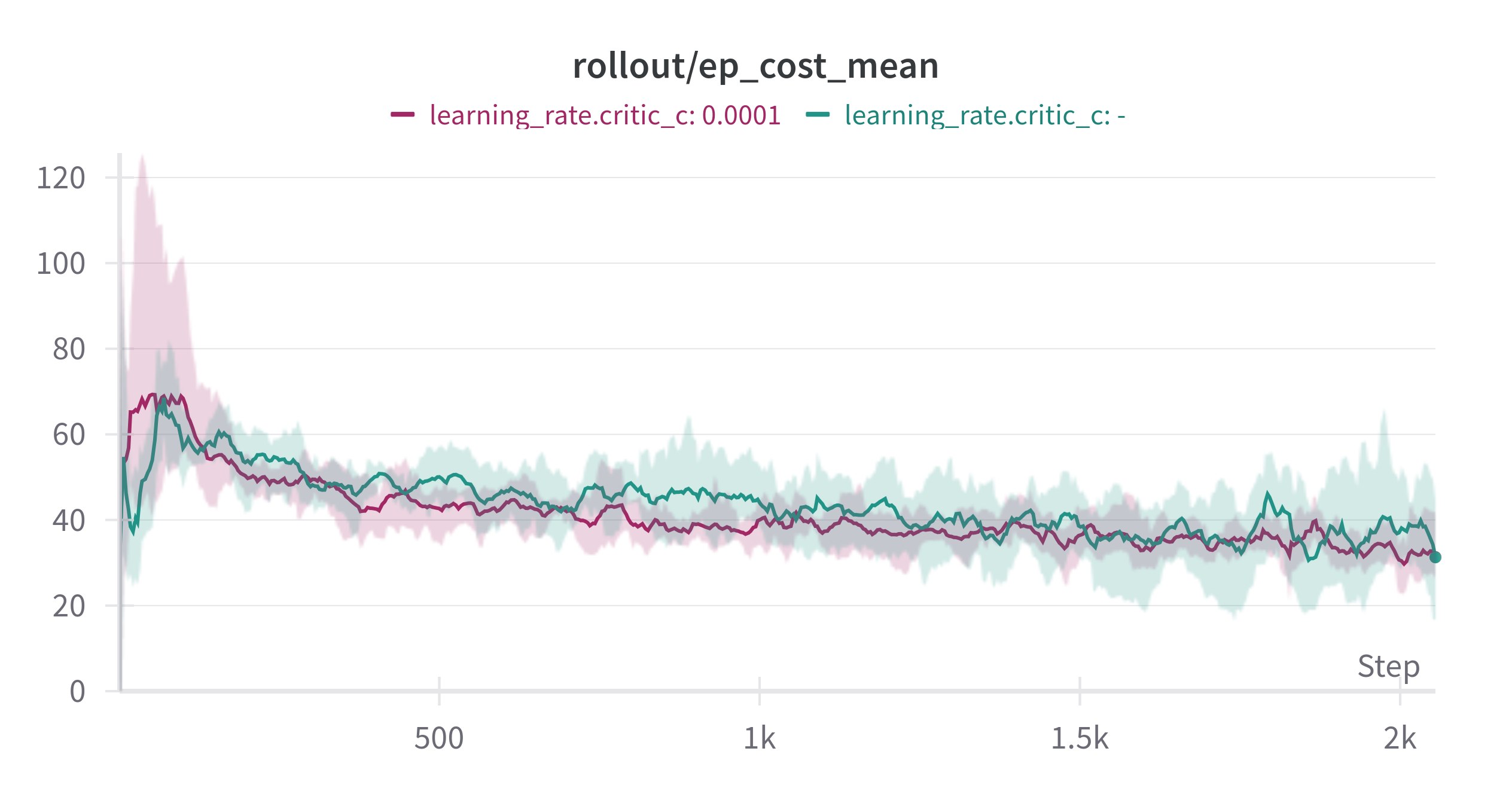

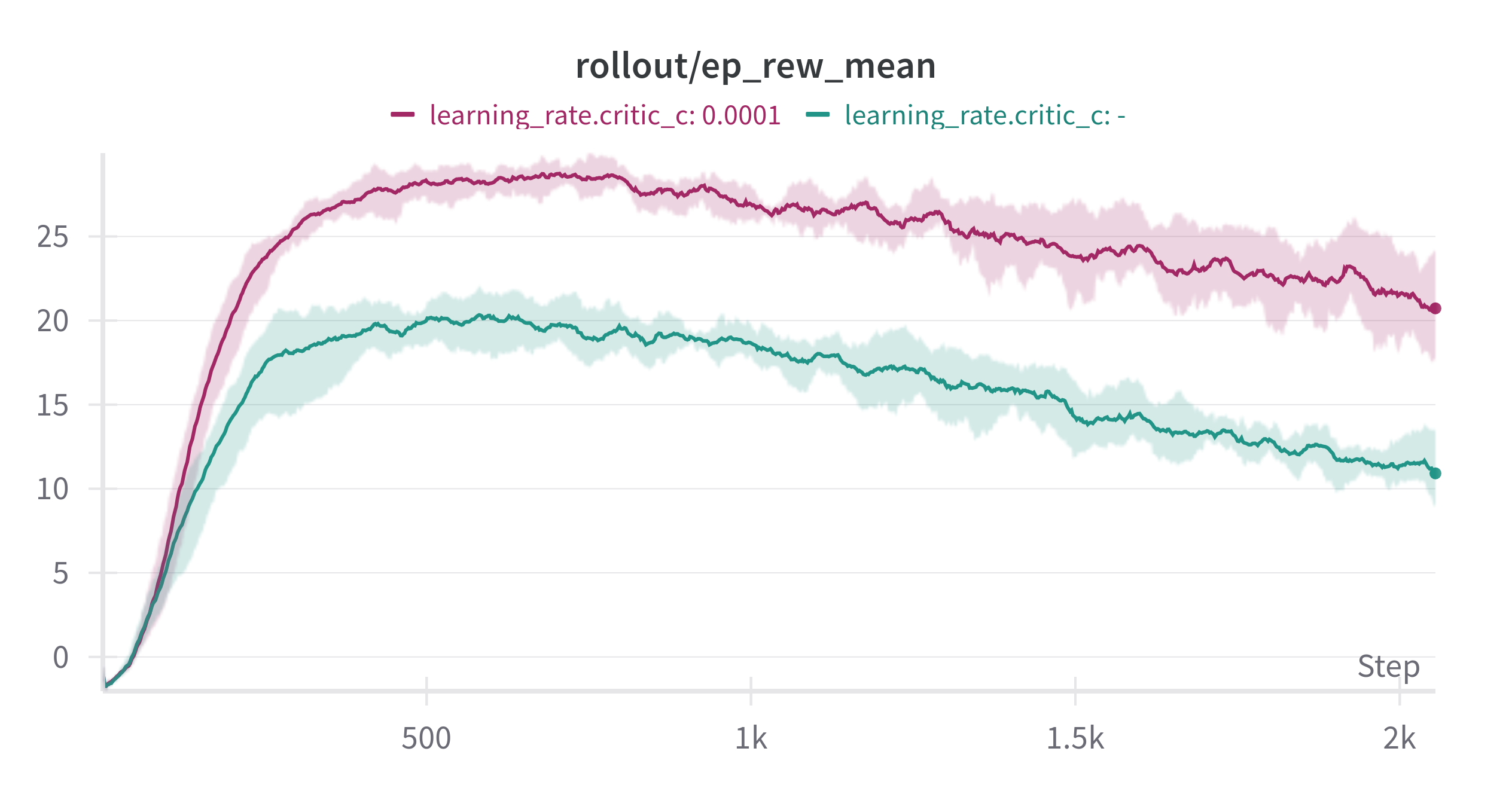

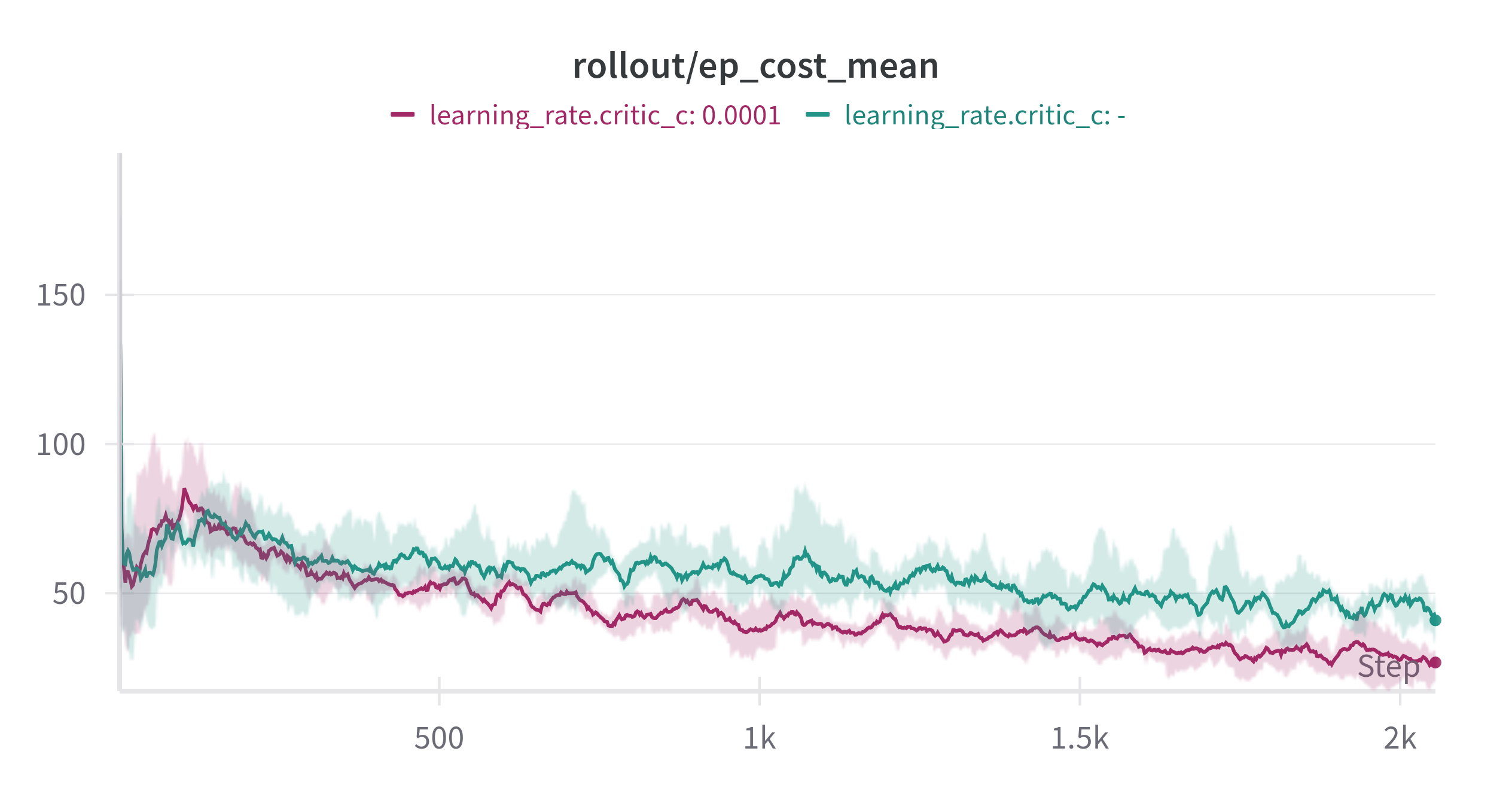

Figure 2: Top: SafetyPointGoal1-v0. Bottom: SafetyCarGoal1-v0. Left: Reward. Right: Cost, both during 5 million training steps with 5 different seeds. Cost limit set to 25. Green label uses the default learning rate of 3e-4. The other label uses a learning rate of 1e-3, three times larger than the actor and reward critic’s learning rate of 3e-4.

I also tested this in a more complex environment: Point-Goal and Car-Goal from Safety Gymnaisum [2]. It generalized well! By setting the cost critic’s learning rate three times higher than the actor, shared features, and reward critic, I saw a huge performance improvement. Of course, all other parameters remained the same. This observation might apply to other RL research, like AMAGO, which also uses shared network structures.

Conclusion

In summary, we have several options,

- Separate Optimizers (No Duplication): Unstable if shared features are only tied to one optimizer, as it ignores their impact on the other.

- Separate Optimizers with Shared Updates: Works well but can be unstable since shared features get updated multiple times per step.

- Single Optimizer (Simple): Stable but may underperform when optimizing multiple objectives with shared structures.

- Single Optimizer with Per-Group Learning Rates: A strong middle ground. Different learning rates for actor, critic, and shared layers address the “one learning rate” problem. It’s practical but requires tuning. If one objective has a larger magnitude, a higher learning rate for that group can help.

The key takeaway: whether using separate optimizers or per-group learning rates, you need to isolate learning objectives to prevent them from interfering with each other.

References

- [1] Raffin, A., Hill, A., Gleave, A., et al. (2021). Stable-Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 22.

- [2] Ji, J., Zhang, B., Zhou, J., et al. (2023). Safety-Gymnasium: A Unified Safe Reinforcement Learning Benchmark. Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track.

- [3] Ji, J., Zhou, J., Zhang, B., et al. (2024). OmniSafe: An Infrastructure for Accelerating Safe Reinforcement Learning Research. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 25.

- [4] Grigsby, J., Fan, L., Zhu, Y. (2024). AMAGO: Scalable In-Context Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Agents. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations.